Contrary to myth, Pennhurst was not a place where evil people wrought intentionally evil schemes. But that makes the meaning even more relevant and the danger even more real: the neglect rising to the level of abuse described in the groundbreaking Pennhurst litigation excerpted below was perpetrated by our own society, in our own backyard, within our own lifetimes. As a former Special Assistant to Pennhurst's Superintendent has said, "Pennhurst was a mistake from day one, but it was a mistake made by all of us, following the dictates of the 'best minds' of its time." Against the backdrop of the state's neglect, countless unremarked acts of kindness from workers and families added bits of humanity to institutional life. It is, no doubt, the resilience of Pennhurst's residents themselves that is the most inspiring part of the institution's story.

Some History

Originally known as the Eastern Pennsylvania Institution for the Feeble Minded and Epileptic, Pennhurst was once seen as a model institution. It was a product of a self-proclaimed "progressive" era when the solution to dealing with disability was forced segregation and sterilization. Since the 18th century - a similarly self-proclaimed age of enlightenment - people with illness and disabilities were labeled "defectives." As late as 1820, such "defectives," along with other dependent "deviant" groups such as aged paupers and the sick poor, were grouped together and sold to the lowest bidder. A similarly conceived philosophy of disposal at the lowest cost was played out time and again at Pennhurst. If only slowly and person-by-person, a growing and maturing society reconsidered this philosophy. History written at Pennhurst demonstrated that what was once held out as the only right option was in fact hopelessly wrong. In contrast to the narratives of intense and prolonged tragedy, Pennhurst's largely untold stories of deep compassion and great character evidence a rise of kind conscience that inspires yet today. One Pennhurst staff member recalls how she and others would volunteer their time on Saturdays and Sundays to clean the residents - many of whom could not toilet themselves - since the state budget did not allocate for housekeeping services on weekends. Another describes sharing holidays at her home with Pennhurst residents whose own families had long since stopped visiting. But, also as shared by a former employee, there is another, rarely considered aspect to the Pennhurst story that is perhaps its most important: the indomitable and unbreakable power of the human spirit displayed every day by the residents themselves.

|

Massive custodial institutions were built to warehouse the retarded for life. The aim was to halt reproduction of the retarded and nearly extinguish their race.

- Justice Thurgood Marshall, 1985

|

Despite the obstacles institutionalization presented, many of Pennhurst's residents found ways to prosper. "They lived lives of inner dignity and grace" in an ammonia-washed world designed to strip that dignity from them. "This was especially true of the individuals who made up the "working patient" group. Day in and day out, they proved their worth helping to care for their worse-off peers by assisting the paid staff in nearly every aspect of life at Pennhurst. Even the most severely disabled found ways to assert their individuality and retain their humanity in the face of a system that dehumanized them in a million different ways. Many people who were told for years that they could not succeed beyond Pennhurst's gates proved the "professionals" wrong, going on to live independent lives of worth and value in the community long after the administration building's great oaken doors slammed shut for the last time. Just as we remember the sadness, we need also acknowledge these quiet triumphs of the human spirit.

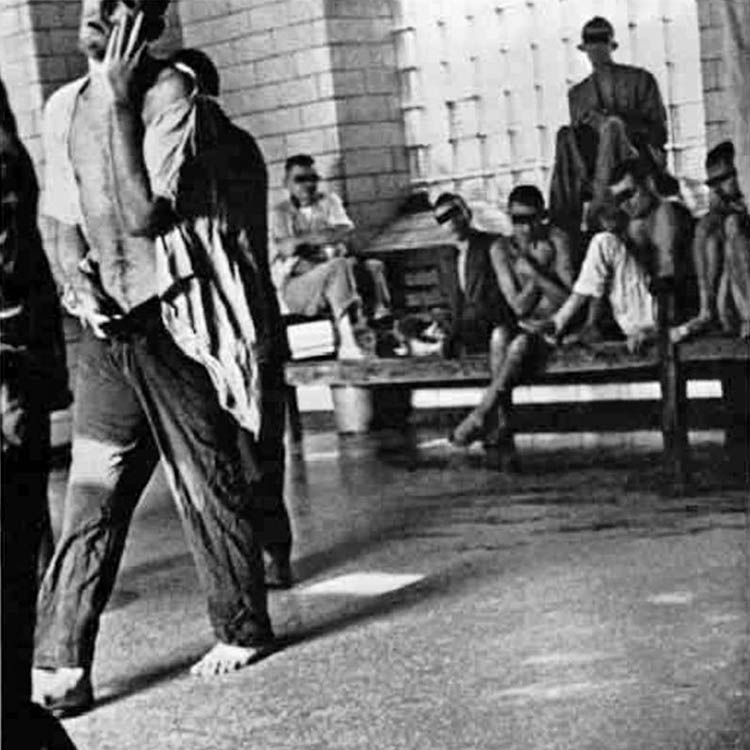

Image from Burton Blatt and Fred Kaplan's Christmas in Purgatory.

Image from Burton Blatt and Fred Kaplan's Christmas in Purgatory.

Excerpts from the facts section of the federal district court case Halderman v. Pennhurst State School and Hospital (446 F.Supp. 1295) demonstrate the horrific conditions lack of funding created at Pennhurst. It was only through the dedication of the overworked staff, it seems, that any humanity at all was afforded in this institution.

Excerpts include:

- No psychologists are on duty at Pennhurst at night or over the weekend, thus, if a resident has an emotional crisis, he or she may go without treatment until the next morning or until the weekend is over.

- At Pennhurst, restraints are used as control measures in lieu of adequate staffing. Restraints can be either physical or chemical. The physical restraints range from placing the individual into a seclusion room to binding the person's hands or ankles with muffs or poseys, and binding the individual to a bed or a chair. Chemical restraints are usually psychotropic (i. e., tranquilizing) drugs.

- Seclusion rooms have been used to punish aggressive behavior. One eighteen year old individual spent six consecutive days in seclusion in 1974 for assaulting a Down's Syndrome resident.

- Often physical restraints are also used due to staff shortages. An extreme example is a female resident who, during the month of June 1976, was in a physical restraint for 651 hours 5 minutes; for the month of August, 1976, was in physical restraints for 720 hours; during September, 1976, was in physical restraints for 674 hours 20 minutes; and during the month of October, 1976, was in physical restraints for 647 hours 5 minutes. (Matthews, Deposition at 64-68). This resident was so extremely self-destructive she totally blinded herself. She was not enrolled in occupational therapy until early 1977. Once initiated, her programming has apparently been quite successful, and she is now able to be out of restraints for as much as four hours per day. (Foster, N.T. 23-43). Had this programming been initiated earlier, her self-inflicted injuries might have been avoided or at least lessened.

- Psychotropic drugs at Pennhurst are often used for control and not for treatment, and the rate of drug use on some of the units is extraordinarily high.

- The physical environment at Pennhurst is hazardous to the residents, both physically and psychologically. (Clements, N.T. 2-59). There is often excrement and urine on ward floors (Roos, N.T. 1-158; Smith, Deposition at 41), and the living areas do not meet minimal professional standards for cleanliness. (Youngberg, Deposition at 24). Outbreaks of pinworms and infectious disease are common (M. Conley, N.T. 16-193; Lowrie, N.T. 4-153; Hedson, Deposition at 122). As Superintendent Youngberg noted:

There is not adequate space for (the residents. The living areas do) not provide privacy for those persons who can handle privacy. There does not seem to be adequate activity areas or program areas or even general activity areas within the general living area or even adequate activity program areas away from the home living area. (Deposition at 23).

- The environment at Pennhurst is not only not conducive to learning new skills, but it is so poor that it contributes to losing skills already learned. (Clements, N.T. 2-59). For example, Pennhurst has a toilet training program, but one who has successfully completed the program may not be able to practice the newly learned skill, and is therefore likely to lose it. (Clement, N.T. 2-36, 2-37). Moreover, most toilet areas do not have towels, soap or toilet paper, and the bathroom facilities are often filthy and in a state of disrepair. Obnoxious odors and excessive noise permeate the atmosphere at Pennhurst. Such conditions are not conducive to habilitation. (Dybwad, N.T. 7-52). Moreover, the noise level in the day rooms is often so high that many residents simply stop speaking. (Clements, N.T. 2-59).

- Injuries to residents by other residents, and through self-abuse, are common. For example, on January 8, 1975, one individual bit off three-quarters of the earlobe and part of the outer ear of another resident while the second resident was asleep. (Matthews, Deposition at 83). About this same period, one resident pushed a second to the floor, resulting in the death of the second resident. (Barton, Deposition at 67, 68). Such resident abuse of residents continues. In January, 1977 alone, there were 833 minor and 25 major injuries reported.(Youngberg, Deposition at 83).

- In addition, there is some staff abuse of residents. In 1976, one resident was raped by a staff person (Ruddick, N.T. 3-115 to 3-117); one resident was badly bruised when a staff person hit him with a set of keys (Barton, Deposition at 40); another resident was thrown several feet across a room by a staff person (Ruddick, N.T. 3-113; Caranfa, N.T. 12-79); and one resident was hit by a staff person with a shackle belt (Bowman, N.T. 13-83; Pirmann, N.T. 19-94). On each occasion, an investigation was conducted and the staff person responsible was suspended and/or terminated (Ruddick, N.T. 3-114; Bowman, N.T. 13-82, 13-83, 13-84; Pirmann, N.T. 19-94).

- Many of the residents have suffered physical deterioration and intellectual and behavioral regression during their residency at Pennhurst. Terri Lee Halderman, the original plaintiff in this action, was admitted to Pennhurst in 1966 when she was twelve years of age. During her eleven years at Pennhurst, as a result of attacks and accidents, she has lost several teeth and suffered a fractured jaw, fractured fingers, a fractured toe and numerous lacerations, cuts, scratches and bites. Prior to her admission to Pennhurst, Terri Lee could say "dadda", "mamma", "noynoy" (no), "baba" (goodby) and "nana" (grandmother). She no longer speaks. (Halderman, N.T. 9-69, 9-71, 9-78, 9-87, 9-88).

- Terri Lee Halderman's medical records contain a listing of over forty reported injuries.

- Plaintiff Charles DiNolfi was admitted to Pennhurst when he was nine years old; he is now forty-five and has resided at the institution continually except for short stays at White Haven State School and Hospital. (Hunsicker, N.T. 9-39). Dorothy Hunsicker, his sister, testified that whenever she or her family visited him, Mr. DiNolfi had some type of bandage on. (Id.) Twenty-six years ago, while at Pennhurst, Mr. DiNolfi lost an eye. A Pennhurst physician told Ms. Hunsicker that Mr. DiNolfi slipped while taking a shower, and hit the spigot with his eye. The sight in his remaining eye has been impaired due to injury. (Id., N.T. 9-46, 9-47). He has only a few teeth remaining and his nose has been battered. (Id., N.T. 9-41).

- Plaintiffs Robert and Theresa Sobetsky were admitted to Pennhurst on November 29, 1971. They were placed on extremely overcrowded wards where beds were placed in the aisles. Robert was never assigned to a particular bed. (Sobetsky, N.T. 9-145, 9-146). During his residency at Pennhurst, Robert Sobetsky suffered from bruises, bites, scratches, welts and he smelled of urine. (Id., N.T. 9-147, 9-148). His record shows a number of reported injuries, some of which, though labeled minor injuries, represented bruises that were three to five inches in length. (Id., 9-151, 9-152). Theresa also suffered such injuries. (Id., N.T. 9-148).

- Since January, 1976, they have been residing at Woodhaven, a Pennsylvania institution for the mentally retarded run by Temple University.

- Plaintiff Robert Hight, born in 1965, was admitted to Pennhurst in September, 1974. He was placed on a ward with forty-five other residents. His parents visited him two and one-half weeks after his admission and found that he was badly bruised, his mouth was cut, he was heavily drugged and did not recognize his mother. On this visit, the Hights observed twenty-five residents walking the ward naked, others were only partially dressed. During this short period of time, Robert had lost skills that he had possessed prior to his admission. The Hights promptly removed Robert from the institution, Mrs. Hight commenting that she "wouldn't leave a dog in conditions like that." (N.T. 11-22, 11-23).

- Plaintiff George Sorotos entered Pennhurst in 1970 at the age of seven. In the seven years that George has been at Pennhurst, his former foster mother, Marion Caranfa, testified that in her weekly visits to Pennhurst there have been only four occasions when George was not injured. (N.T. 12-63). During this period, he has suffered from numerous reported injuries, including bites, scratches, black eyes and loss of teeth. In addition, Mrs. Caranfa testified that she recently observed what appeared to be cigarette burns on George's chest. (N.T. 12-65).

- The Caranfas were made George Sorotos' foster parents when he was six weeks old. Sometime after he entered Pennhurst, the agency which had supervision over George removed them as his foster parents. They still consider him as one of their family and have continued their visits. (Caranfa, N.T. 12-62, 12-105).

- Plaintiffs Larry and Kenny Taylor entered Pennhurst on February 28, 1961. In the early 1970's, Mrs. Taylor questioned the staff about the medication being given to Larry. He was very lethargic, falling asleep at school and barely able to walk. (Taylor, N.T. 13-24). The physician in charge of Larry's unit, checked Larry's medical record and found that he was on dilantin, a drug used to control epileptic seizures. Mrs. Taylor testified that Larry had had only one seizure that she knew of and that had been when he was a baby. Larry was removed from dilantin and placed on mellaril, a psychotropic drug. This, too, made him lethargic. (Id., N.T. 13-26 to 13-28). Larry and Kenny were transferred to Woodhaven in 1975 where Mrs. Taylor testified that Larry does not receive any psychotropic medication, and is able to walk independently. (Id., N.T. 13-32). Larry was often injured while at Pennhurst; on one occasion, he was hospitalized for two weeks because of head and face injuries he received as a result of a beating by another resident. (Id., N.T. 13-30). Kenny, too, suffered serious injuries while at Pennhurst. (Id., 13-29).

- Plaintiff Nancy Beth Bowman entered Pennhurst at the age of ten in 1961. She was placed on a large ward which had sixty-five residents and often only two child-care aides in attendance. (Bowman, N.T. 13-71; Pirmann, N.T. 19-89). During her residency at Pennhurst she developed maladaptive behavior, i. e., biting and pushing. (Bowman, Id.) As a result of this maladaptive behavior she has been placed in seclusion for days at a time. (Id., N.T. 13-71). While at Pennhurst, she has lost teeth, been badly bruised and has been abused by the staff. (Id., N.T. 13-72, 13-73, 13-81). When asked about her present physical condition Nancy Beth's mother replied, "Nancy Beth will be scarred for the rest of her life." (Id., N.T. 13-94).

- Plaintiff Linda Taub, who is blind in addition to being retarded, was admitted to Pennhurst in 1966 at the age of fifteen. According to her father, during her nine year residency at Pennhurst Linda received only custodial care and she experienced regression rather than growth. (Taub, N.T. 2-170). Time on the ward was spent sitting and rocking, with few activities. (Id., N.T. 2-155). During one of their visits in 1968, Linda's parents found Linda, a person capable of walking, strapped to a wheelchair by a straightjacket. A staff member explained that by strapping her into the chair, they would know exactly where Linda was. (Id., N.T. 2-152, 2-153). While at the institution, Linda was badly bruised and scarred. (Id., N.T. 2-164).

- Approximately 21 of the 45 living units at Pennhurst are locked (Matthews, Deposition at 34) to prevent individuals from leaving their living units. (Uphold, Deposition at 139). Those individuals over the age of 18 who have been "voluntarily" admitted to Pennhurst are theoretically free to leave the institution at any time. (Allen, N.T. 21-185). Those admitted on the petition of their parents are informed by their caseworker when they reach the age of 18 that they do not have to remain at Pennhurst. If the residents state that they wish to leave the institution and the staff determines that there is no place for them in the community, or believes that the individuals are not ready to go into the community, the staff will petition the courts to have the individuals committed to the institution by a court. (Id., N.T. 21-186, 21-205). Furthermore those residents who either do not understand their alternatives, or are physically unable to indicate that they wish to leave Pennhurst, will be deemed to have consented to their continued placement at the institution. (Id., N.T. 21-210). Thus, the notion of voluntariness in connection with admission as well as in connection with the right to leave Pennhurst is an illusory concept. Few if any residents now have, nor did they have at the time of their admission, any adequate alternative to their institutionalization. As a practical matter, Pennhurst was and is their only alternative. Nearly all the parents of Pennhurst residents who testified stated that they placed their children in Pennhurst only as a last resort, and had there been community facilities or aid programs, their children would not have been placed at Pennhurst. (Sobetsky, N.T. 9-142; Hight, N.T. 11-21).

Click here to review the complete transcripts from the Halderman vs. Pennhurst case.